When Zahra Noorbakhsh was 14 and living in Dansville, California, her Iranian immigrant mother learned she was defying the family ban on dating by going to a movie with a boy. And thus began a particularly entertaining sex talk between mom and daughter.

“Zahra, you have a hole,” said her mom. “For the rest of your life, men will want to put their penis in your hole. It doesn’t matter who you are, what you look like, who is your ‘friend.’"

To which Zahra responded: “I have a what?! A hole? Where? Was that what I had missed in sex-ed the one day I had the flu?”

This anecdote, shared in the essay anthology Love, InshAllah: The Secret Love Lives of American Muslim Women and frequently performed on stage by Noorbakhsh, gets at the heart of her particular brand of comedy—one that explores the intersection of feminism and the Muslim faith through the lens of humor. But the real hat trick here is that she manages to share this unique experience in a way that resonates with people of all backgrounds and perspectives.

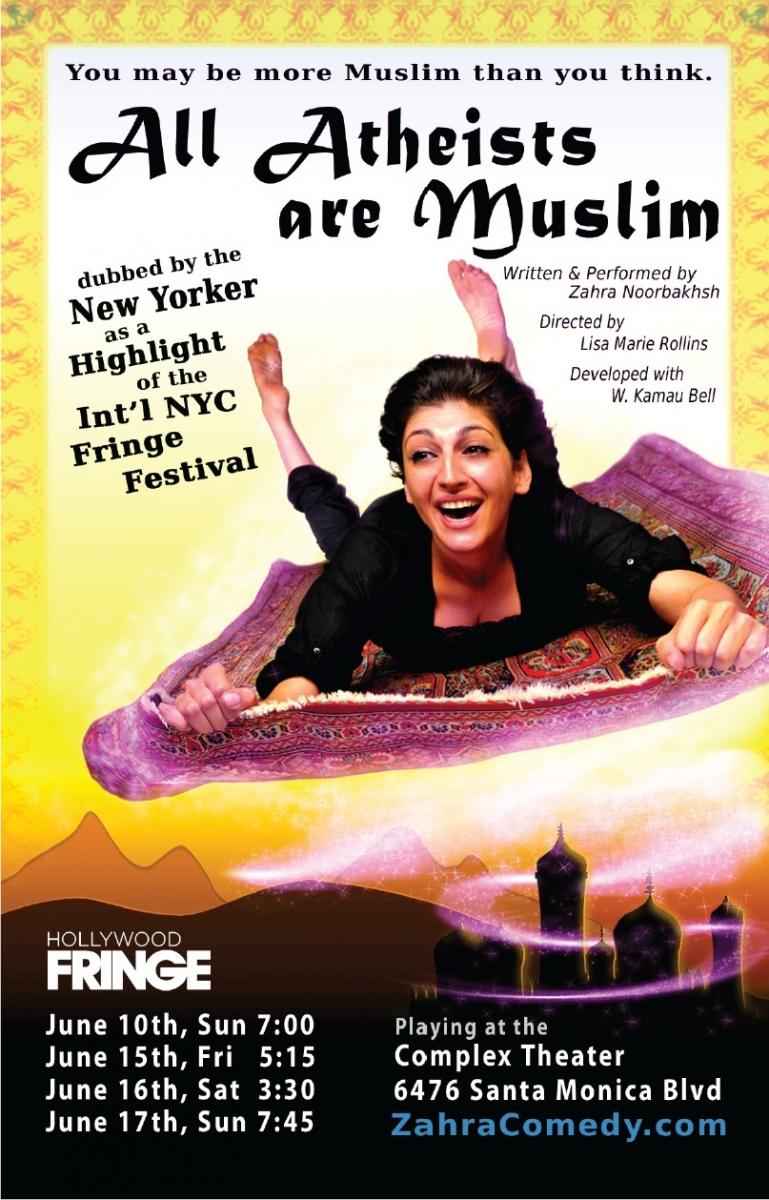

It's a brand of comedy that's served Noorbakhsh well. The New Yorker Magazine dubbed her one-woman show "All Atheists Are Muslim" a highlight of the International New York City Fringe Theater Festival, and she'll be performing her new one-woman-show, "Hijaband Hammerpants," at Stage Werx Theater in San Francisco on Nov 20.

We spoke with Noorbakhsh about how her faith has shaped her, why she identifies as feminist, and the time she wore a hijab to a Blockbuster . . . then made a play out it.

"All Atheists Are Muslim," a comedy show about a Muslim woman moving in with her atheist boyfriend, is, according to you, "90% true." How did your actual experience differ from the one presented in the show? And was it cathartic, difficult—or both—to share this personal story on stage?

Sharing “All Atheists” was life-altering. When I was crafting the full-length show with my-then director W. Kamau Bell, I remember asking him, “Is anyone going to get this?” I realized that despite all of the Islamophobia-spouting talking heads in the media, there was a huge community of allies that were starving for a story that is true and full of love. After the show, I heard about in-laws and children, and met quite a few Irish Catholic grandmas in the audience, who felt like they were hearing themselves speak through my Muslim-Iranian dad. It was an amazing experience touring it.

So, what’s the 10% of the show that’s not true? Well, my parents’ names are different. And their “love story” is sped up. I exaggerate it in a fairytale-type-telling. Also, it took [my boyfriend] Duncan a month to move in and not two weeks as I say in the story. Though, I did put off telling my parents about it until I had two weeks left.

You've also penned and performed a play, "Hijab and Hammerpants," about the time you wore a hijab to a Blockbuster store when you were younger. How did that experience shape you? What made it significant enough to turn it into a play?

I’m so sick of hearing stories and debates about hijab that don’t involve choice, ambivalence and all the complexity around the decision to wear it. Hijab makes Muslim women, who are often seeking modesty, so hyper-visible. The story of hijab is really every woman’s story, where what we wear and how we look take away our ability to choose our identity. I don’t advocate veiling or unveiling. I think it should be a women’s choice and everyone else should shut the hell up. These feelings are made clear through my story. And, you also learn why sometimes banana yellow MC hammerpants can make you even more of a pariah in an American public school in the Bay Area than hijab.

How do you manage to find humor in dark, uncomfortable, complex questions surrounding issues like religion, women's rights and identity? Why use comedy to address these topics?

Comedy is the universal language. We don’t laugh unless we really “get it.” I love the irreverence of satire and religion takes itself so damn seriously, it’s hard for a punk kid like me not to love poking at it. Also, the anti-Islamic rhetoric and anti-feminist sentiment that is in mainstream discourse is so absurd, how can it not be funny?

When did you first realize that you were "funny"—and that you wanted to make a career of it?

I went to a different elementary school every year. In third grade, I was in two different elementary schools, one in the fall, and then we moved in spring. As an extroverted kid I was always trying to be funny, be liked and fit in at the new school I wound up at.

You've stated that "being raised Muslim has shaped my entire sense of humor, my outlook, my upbringing and the values I uphold." How so?

It was the religion I grew up with and its folklore and values were how I related with the world. Justice is an important value in Islam, and it is for me. Democracy was a factor in Islam’s inception, and being an activist, being heard is a value I uphold. My father used to repeat over and over again that in Islam, there is no person between you and God—that no one has a right to step in on this relationship. Those words fuel me and my work today.

Why do you identify as feminist? And has that identity created any conflict in your life?

I identify as a feminist because I am a woman who values other women. Any woman who doesn’t identify that way is a fool. Apart from that, my feminist community has always had my back. Does it create conflict in my life? Absolutely. Mostly, it comes up as an issue in comedy, where being a funny woman is oh-so-surprising.

You often perform at schools. How does your work resonate with the younger generation?

“All Atheists Are Muslim” resonates with college students because it takes place in college and it’s also a common experience to have to reveal to your parents that you’re with someone they won’t “approve of.” I think my favorite comment was from a young woman who asked me why I was worried about Duncan’s family accepting me, because “I look white.” As soon as she said the words out loud she realized what she was implying, and so did the whole room of young, white, Christian women who were thinking it and finally hearing how absurd it was.

What's next for you?

I’m working on a memoir that fuses both “All Atheists Are Muslim” and “Hijab and Hammerpants” into one story. A memoir is an epic undertaking and it’s hard for me to write in private. I’m so used to having an audience to bounce off of. It’s a new adventure.